The last chapter looked at ex-KGB officer Nikolai Leonov’s account of meeting accused JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City on Sunday, Sept. 29, 1963. Fellow KGB officer Oleg Nechiporenko claimed he and fellow consular officials dealt with Oswald — without Leonov — on Friday and Saturday, Sept. 27-28. No one has ever resolved the discrepancy, and the Russians have never produced the report that Nechiporenko claims he and his KGB-consular colleagues sent to Moscow Center about Oswald’s visit. That file should be among those requested from the Russian government by the U.S. House Oversight Committee’s Task Force on the Declassification of Federal Secrets.

From Peasantry to Commanding Heights

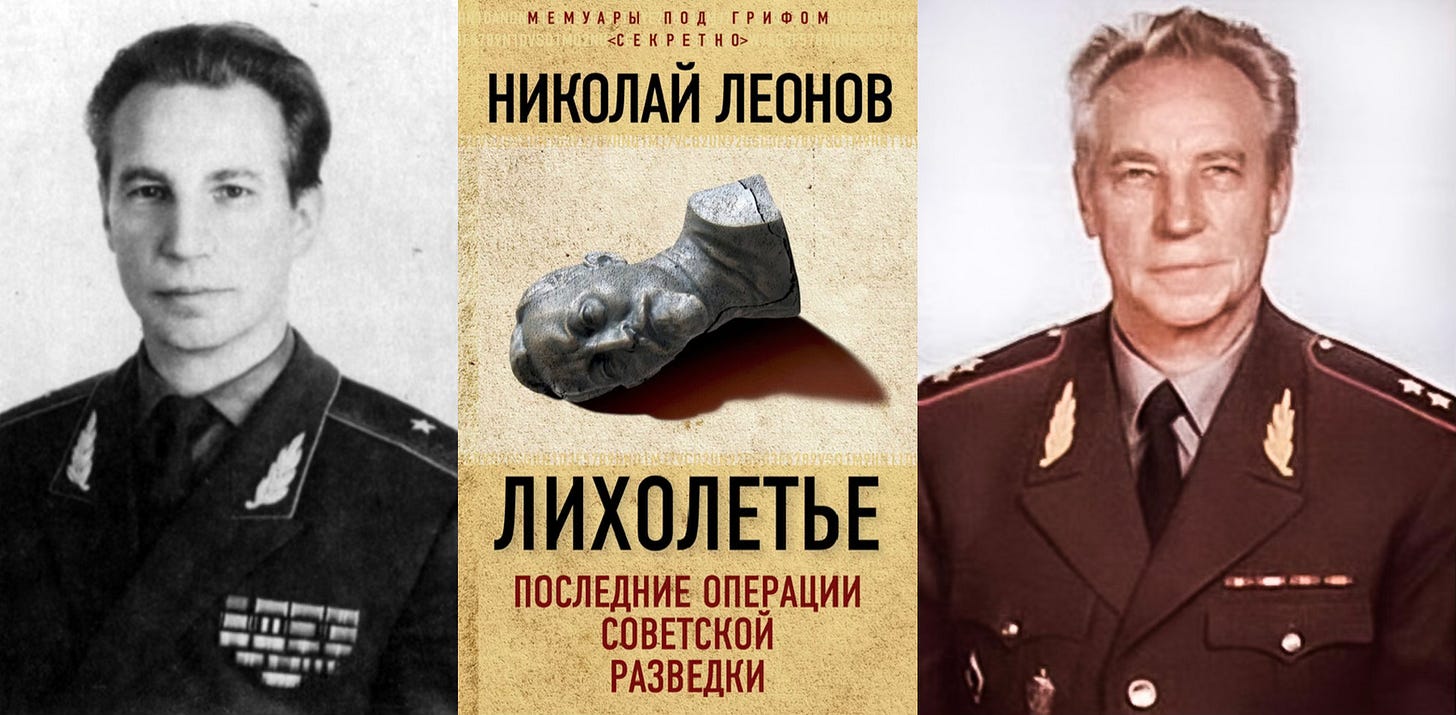

While Nechiporenko reportedly retired from the KGB with the rank of colonel, Leonov retired as a lieutenant-general. By the time he resigned on Aug. 26, 1991, he was the number three man in the Soviet KGB after the politically-appointed chairman and the head of the First Chief Directorate, which ran foreign intelligence. As that directorate’s “first deputy chief” and head of analysis for the entire agency, Leonov finished his professional spy career as the 2nd-highest functionary in the KGB apparatus itself.

Leonov had risen to the top of the Soviet system from very humble origins. Born to a peasant family in a village about 170 miles south of Moscow in 1928, he graduated from Moscow’s State Institute of International Relations in 1953, then angered the Soviet foreign minister, Andrey Vyshinsky (prosecutor during the 1930s Stalinist show trials). Banned from a career in the foreign ministry, Leonov was sent (or exiled) to Mexico on an academic internship. On the voyage across the Atlantic, he met someone who would play an important role in Latin American politics in coming years: Raúl Castro.

In 1956, as a postgraduate student at the University of Mexico (and part-time embassy intern), Leonov met another key Cuban figure, Ernesto “Che” Guevara. When Mexican police arrested Guevara and Fidel Castro with other Cuban revolutionaries in Mexico City, they found Leonov’s calling card in Che’s wallet. Recalled from Mexico, Leonov returned to Moscow to work at the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences and soon received an invitation to train with the KGB. The following year he returned to Mexico as a full-time spy.

That year, 1959, Soviet First Deputy Prime Minister and Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan visited Mexico, and the delegation included Leonov. In 1960, when Mikoyan visited Cuba, Leonov — whose Spanish was near-flawless — acted as his interpreter. He performed that function when Fidel Castro visited the U.S.S.R. in spring 1963.

Until 1969, Leonov would operate full-time in Latin America, spearheading the Soviet intelligence penetration of the Western Hemisphere. Outwardly, he was a lowly embassy official. Under cover, the rising KGB officer had already attracted the attention of the CIA.

As Bill Simpich writes in Chapter 5 of “State Secret,” under a CIA program codenamed TARBRUSH, the Agency tried “on at least three separate occasions during 1963-64 to make Leonov look bad,” after Soviet KGB defector and CIA asset Anatoly Golitsyn identified Leonov in 1962 as “a KGB officer presently assigned to Mexico City.” It turned out Leonov was an extremely important target for the CIA, probably more so than Valery Kostikov, the vice consul that the CIA alleged to be in charge of assassinations for the KGB in the whole Western Hemisphere (Kostikov and Nechiporenko denied that).

Angleton, Oswald, and Leonov

Former CIA Counterintelligence Chief James Angleton’s (probably faulty) memory of TARBRUSH led him to spread the unfounded allegation to Congress in 1975 that Oswald had been arrested in Mexico City with a photo of Leonov in his pocket. Angleton also made the unsubstantiated statement that Oswald’s purpose in traveling to Mexico City was to go directly to Cuba to contact the Soviets from there.

Whether Angleton was dissembling or confused (he called Leonov “Leontov”), he probably conveyed a few more untruths under oath. One of them concerned Yatskov, whom he described as the “chief of KGB, Mexico” and “a superior of Leontov.”

Consul Pavel Yatskov may have outranked Leonov within the KGB in the early 1960s (Yatskov was in his early forties at the time of the assassination; Leonov was only 35). But the “chief of KGB” (head of the rezidentura) in Mexico City in 1963 — according to the KGB’s own information — was someone named Vladimir Konstantinovich Tolstikov.

Angleton also referred to “Byetkov,” saying he didn’t know whether Leonov was in Mexico City during Oswald’s visit “because the double agent whom we believe was actually controlled by the Soviets, Byetkov, gave us information which we would now regard as private, which would tend to absolve the Soviets of any implication with Oswald.”

He was probably referring to Ivan Obyedkov, the embassy’s chief of security and also a KGB officer. Angleton seemed to be trying to resurrect the unfounded conspiracy theory that the Soviets were somehow behind President Kennedy’s murder by citing the KGB’s denials to that effect. It was as if — because KGB officers, like their CIA counterparts, were trained to lie — the opposite of their denials was true: they convinced Oswald to kill JFK.

In the caption to the above photo in his book, Nechiporenko writes that Obyedkov’s telephone conversation with Oswald on Oct. 1, 1963, “was recorded by the CIA” and cites Edward J. Epstein’s Oswald-dunnit book, “Legend: The Secret World of Lee Harvey Oswald” (1978), as his source. But Nechiporenko also says that Obyedkov told him on June 9, 1993, that he “could not remember having such a conversation.” Since only a CIA transcript of the call identified Obyedkov, there was no way to verify his voice.

During the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) investigation in the late 1970s, the CIA employees in Mexico City who transcribed wiretapped phone conversations to and from the Soviet Embassy testified that the voice claiming to be “Oswald” in a call on Tuesday, Oct. 1, 1963, was the same one that called that embassy the previous Saturday, Sep. 28, supposedly from the Cuban consulate.

Yet Cuba’s embassy was closed that day and received no visitors. The Soviets would later say no calls were accepted from any outsiders on the weekend as well. Again, only transcripts survived. The CIA told investigators the tapes had been “routinely” destroyed.

Furthermore, transcript notations indicated that the caller spoke in “broken Russian,” so bad that the native Russian-speaking CIA transcriber had trouble understanding him. The man gunned down by Jack Ruby on Nov. 24, 1963, was fluent in Russian. The transcriber also told the HSCA that whoever made the Oct. 1 call reminded him of a “coiled snake ready to strike,” but “a very cool individual” at the same time. None of this sounds like the nervous young man Jack Ruby shot to death in Dallas police custody. In other words, an impostor pretended to be Oswald over the phone to the Soviets in Mexico City.

Since Obyedkov could remember no such call, was the transcript altered or fabricated, at least in part? One of the husband-and-wife CIA transcriber team said she distinctly remembered “Oswald” requesting money from the Soviets, yet there is no record of that in any of the CIA transcripts provided to official investigators.

And did Angleton really not know Leonov’s whereabouts when Oswald was supposed to have been at the Soviet Embassy, or when Oswald was supposed to have called there on Tuesday, Oct. 1, 1963, according to a transcript provided by the CIA? The CIA’s own surveillance photographers captured Leonov entering the embassy the very next day.

Through an intermediary, JFK Facts editor Jeff Morley tried to contact Leonov many years ago but received the response that under no circumstances would Leonov ever deign to talk to an American. Nechiporenko might still be alive at 92; Leonov died in 2022 at 93.

Leonov’s Motive

In the 2015 edition of his memoir, “Hard Times,” Leonov unapologetically makes the case for the glory and virtue of the Soviet enterprise. He defends principled Soviet intelligence officers as valorous agents of the “socialist commonwealth,” acting selflessly, without regard for material reward or privilege. “Hard Times” is a proud Soviet Russian’s chronicle, and Leonov’s professional life in the KGB was likely an illustrious adventure.

Leonov lamented the degradation and demise of the U.S.S.R. at the hands of petty apparatchiks and corrupt time-servers. They had allowed the Soviet Union to disintegrate, he said, under the weight of CIA-led Western intelligence plots and lies. As the union was coming apart, Leonov appealed to the Supreme Soviet (parliament) to act. Promoted to lieutenant-general the day before the State Committee for the State of Emergency in the USSR led a failed putsch against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991, Leonov resigned from the KGB a few days after the coup attempt was over.

After the U.S.S.R. was no more, Leonov took a position at the Academy of Sciences of the Russian Federation, then served as a member of the lower chamber of Russia’s parliament, the State Duma, representing the “Narodnaya Volya” (People’s Will) party in the “Rodina” (Motherland) bloc of nationalists from 2003-2007.

He remained in parliament until age 79, still writing books, including “Russia’s Way of the Cross” (2005). Christianity was not, he claimed, incompatible with the Soviet experiment. He wrote of American friends in Mexico who circulated the slogan, “Yes to Christianity, No to Communism” at the behest of “right-wing forces.”

And I showed them the New Testament, the sacred book of Christians, opened the “Acts of the Holy Apostles” (Ch. 4, Verses 32 and 34), and read about the first Christian communities created by Peter and John: “And the multitude of them that believed, were of one heart, and of one soul; neither any of them said, that anything of that which he possessed, was his own, but they had all things common … Neither was there any among them, that lacked, for as many as were possessors of lands or houses, sold them, and brought the price of the things that were sold.” The authority of the Bible disarmed even hostile opponents. (“Hard Times,” p. 43)

He wrote of how these Americans were “surprised at how a socialist society, rooted in early, and therefore genuine, Christianity, managed to earn a reputation for being godless and anti-Christian.” At the same time, the falsely pious Western leaders “adopted Christianity and manipulated it for their own pleasure.”

Given who Leonov was, it is easy to see why he would adopt, in part, Nechiporenko’s fanciful tale of the Oswald “revolver incident,” modifying it to involve only himself, and then — most importantly — use it to express his opinion that the man accused of killing President Kennedy was a patsy. Leonov spoke English and may have encountered Oswald on Friday, Sept. 27, 1963, since part of his job at the time was greeting foreign visitors inside the main embassy building. But he wouldn’t besmirch his beloved KGB by completely negating Nechiporenko’s unlikely story of Oswald’s weekend visit.

If Oswald was a pawn in a plot, as Leonov said Soviet intelligence had concluded, the weight of worldwide opprobrium would fall primarily on the U.S. government (especially the CIA) for covering up a conspiracy. That image of America served Leonov’s interests. He continued to view the United States as an enemy of Russia after the end of the Cold War and until his death. It just so happened that, motivations aside, Leonov’s version of events regarding JFK’s death was closer to the truth than what Nechiporenko was selling.

Lies All Round

Nechiporenko needed to ingratiate himself with U.S. authorities to get a book deal with Birch Lane Press, a publisher of sensational exposés and fiction for adults in 1993, now best known for children’s books. In the wake of the Soviet collapse, amid the unspeakable sorrow and depredation in Russian society, when Moscow was desperate for foreign cash, he very likely coordinated his story with post-Soviet Russian intelligence as well. In other words, Nechiporenko went through two sets of censors to get a book out in America.

Thus, he upheld the Warren Report’s bogus “lone gunman” theory. As a retired KGB colonel (likely promoted to that rank immediately prior to his retirement), he couldn’t count on a cushy future in the absence of anything else. If, however, he had met an American who had brandished a gun inside a Soviet embassy before finding himself accused of assassinating a U.S. president, he could at least count on a decent advance to spin his yarn, even if his book never made it to paperback.

There is no evidence Leonov ever became a billionaire oligarch, but at his level of the Soviet hierarchy, he could move into the post-Soviet era in some comfort. Members of the Russian parliament generally live in a sort of splendor relative to ordinary Russians. Well into old age, Leonov still traveled abroad, talking about his life to interested audiences. He never saw any need to come forward about what really took place in Mexico City in the early fall of 1963, since he never felt he owed America anything, including the truth.

The next installment of “Oswald and the KGB” will speculate on what really happened at the Soviet and Cuban embassies in Mexico City when Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly visited them in the fall of 1963.

[Part IV of the six-part series, “Oswald and the KGB,” can be read here.]

So much research on this subject that many who are interested in the less obvious aspects of this story would never know. Thank you Chad for your work and sharing your findings.

Thank you Chad. I wonder if I told you about the KGB linked Gardos at Corvina Books in Hungary who in 1963 was mentioned in the Tippit Call...I found him mentioned as some Corvina writer was approached by a Gardos relative from the US...in 1964...but he could have been a KGB officer pretending to come from the US...of course this weird marginal story can only been researched in the [ now closed] Moscow Security Archive. So I wrote just to mention it because I do not see any way to let this be known.