Oswald and the KGB — Part IV

Another installment in the series on what happened in Mexico City in the fall of 1963

Originally intended as a four-part series, “Oswald and the KGB” now needs more space to tell its story. As such, this won’t be the final episode. The alternative was making this one far too long for a single sitting, and readers need a pause for contemplation. So do I.

To recap, the man shot to death by Mob-connected Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby on Nov. 24, 1963, may or may not have visited Mexico in the fall of 1963. Lee Harvey Oswald denied to police and FBI that he had ever been anywhere in Mexico in his life except Tijuana, and his movements in the days leading up to Friday, Sep. 27, 1963, are unclear. Someone impersonated him in Mexico City, and some alleged sightings of him in Texas seem to preclude his appearance at the Soviet and Cuban embassies on that day.

That said, we do know Oswald lied on occasion. We also know that at the time of his alleged trip, the CIA and FBI were jointly trying to subvert and destroy the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), the Castro-friendly New York-based organization that Oswald claimed to represent in New Orleans. As either a witting or unwitting “agent of influence,” the young ex-Marine and ex-defector to the U.S.S.R. could have furthered such a propaganda operation whether he ever went to Mexico in person or not.

Either the man shot by Jack Ruby went to Mexico City, or someone armed with his “legend” did, perhaps a lookalike, posing as Oswald with documentation to prove it. That means discussion of Oswald really refers to “Oswald,” either the real man or an impostor, but his name will not appear in quotation marks in every instance in this study.

Finally, we know that the CIA’s counterintelligence chief, James Angleton, was desperate to catch a mole in his agency, and since his office tightly controlled the CIA’s already voluminous file on Oswald, he likely intended Oswald to further that objective in Mexico City. In other words, there was a twofold purpose to Oswald’s trip, only Oswald’s “mission” didn’t turn out to be as “secret” as Angleton would have liked.

Leonov’s Clues

Ex-KGB officer Nikolai Leonov’s memoir, “Hard Times” (2015), contains three lonely consecutive paragraphs dealing with the “Oswald encounter” in Mexico City. They provide no hard evidence of what really took place in light of the inconsistent account of his colleague, Oleg Nechiporenko, in “Passport to Assassination” (1993). However, on either side of this small section in his book, Leonov hinted at how he viewed the affair.

Three paragraphs before telling his Oswald tale, Leonov says:

Since the beginning of the 60s, American intelligence services began to actively throw false well-wishers — provocateurs — into our embassy.

He then gives examples of Americans who offered their services to Soviet intelligence, but who, for one reason or another, failed to convince the KGB of their sincerity. The implication: the KGB in Mexico City was accustomed to provocateurs, and Oswald’s visit to the Soviet Embassy was a provokatsia — or provocation.

After the third paragraph discussing Oswald, Leonov writes that he and his fellow KGB officers “never forgot for a minute that we ourselves were the object of close attention from the American special services,” and that the Americans probably “rented a floor or at least an apartment building closest to the entrance to the Soviet embassy.”

The windows of this room remained constantly draped, regardless of the weather. The curtains hid surveillance and secret photography equipment.

This equipment, Leonov wrote, took photos of “everyone entering and leaving the embassy.” Even Nechiporenko wrote that when Oswald exited the front gate on Saturday, he tried “to avoid being clearly photographed.” So, not only did the KGB in Mexico City assume the CIA was monitoring them. They were also on guard for provocateurs.

The Russians would have treated the witting or unwitting provocateur as a durak. That term usually gets translated into English as “fool” but has a more philosophical connotation in Russian culture and folklore. Manipulators of “Ivanushka Durachok” (his surname an affectionate diminutive of durak), a protagonist in Russian fairy tales, sometimes find their own schemes backfiring on them. Oswald, not yet 24 years old in September 1963, fit the durak profile. The Russians would have treated him as one — not harming him, but dealing with him and sending him clueless and bewildered on his way.

As such, what transpired in Mexico City was the result of a CIA operation gone awry at the hands of the KGB and G-2. That is, Soviet and Cuban intelligence “fooled” the CIA.

Oswald and the Mole

Prof. John Newman, author of “Oswald and the CIA” (2008), published a book in his series on the JFK assassination called “Uncovering Popov’s Mole” (2021). It doesn’t deal with Mexico City, but it does — perhaps inadvertently — add insight into what transpired there in connection with the man who would be accused of killing JFK.

Newman posits the theory that Oswald’s defection to the Soviet Union in 1959 wasn’t just fake; it was actually orchestrated by a Soviet mole inside the CIA. Hoping Oswald’s defection would further the mole hunt, Angleton mistakenly assumed that the mole had to be located in the CIA’s Soviet Russia Division. In reality, Newman claims, he was operating from inside its Office of Security. Angleton trusted this CIA officer unreservedly until he (Angleton) was fired at the end of 1974. That officer, Bruce Solie, retired in 1979.

The purpose of deploying a “dangle” is not to catch someone interacting with him in the field, but rather to catch someone at headquarters inquiring about him. “Dangling” Oswald, Newman says, was doomed to fail: no mole would give themselves away by requesting Oswald’s file once news of his defection had circulated, because the mole was the one who had arranged Oswald’s defection to the U.S.S.R. in the first place.

Angleton likely hoped that, by approaching an embassy of America’s Cold War enemy outside U.S. borders, Oswald would raise the mole’s antennae. By repeating his pro-Castro leafleting and posturing of less than two months earlier in conservative and highly anti-Communist New Orleans, the disreputable ex-defector Oswald — undesirably discharged from the U.S. Marine Corps — would hopefully also shame the FPCC in Mexico, where popular sympathy for the Cuban Revolution ran high.

But this clever scheme to use Oswald to unnerve the KGB and G-2 (Cuban intelligence) in Mexico City was bound to run into trouble if the Soviet mole at Langley had already made sure the Mexico City KGB rezidentura knew Oswald was headed their way.

KGB Tip-Off

Nechiporenko also provides a clue that the KGB in Mexico City was expecting Oswald. When discussing his first meeting with the American on Friday, Sep. 27, he says:

Even though I had seen the letter to our embassy in the United States, I nonetheless asked him if he had appealed to the Soviet embassy in Washington. Oswald said that he had already sent a letter there and had been turned down. (p. 70)

Why would a Soviet vice consul in Mexico, even an undercover KGB officer, have any information on an American’s application for a visa to the U.S.S.R. inside the United States? Was it standard protocol to share with the KGB rezidentura in Mexico City a letter from an American in Texas to the Soviet Embassy in Washington? Nechiporenko never explains why he would have seen such a letter or when, and in a later passage he even says that he and his two KGB colleagues in Mexico City “had no prior information” on Oswald when he appeared at the embassy on Sep. 27, 1963.

But in telling us he knew in advance who Oswald was and what he was doing in America, Nechiporenko betrays a priori familiarity with the young American. That suggests the KGB in Mexico City had a plan in place for how to deal with the “dangle” when he arrived at their front gate. They would make sure the CIA’s attempts to use Oswald to flush out their mole at Langley and undermine the reputation in Mexico of an organization favoring friendly ties between the U.S. and a Soviet ally — Cuba — backfired.

The No-Photo Quandary

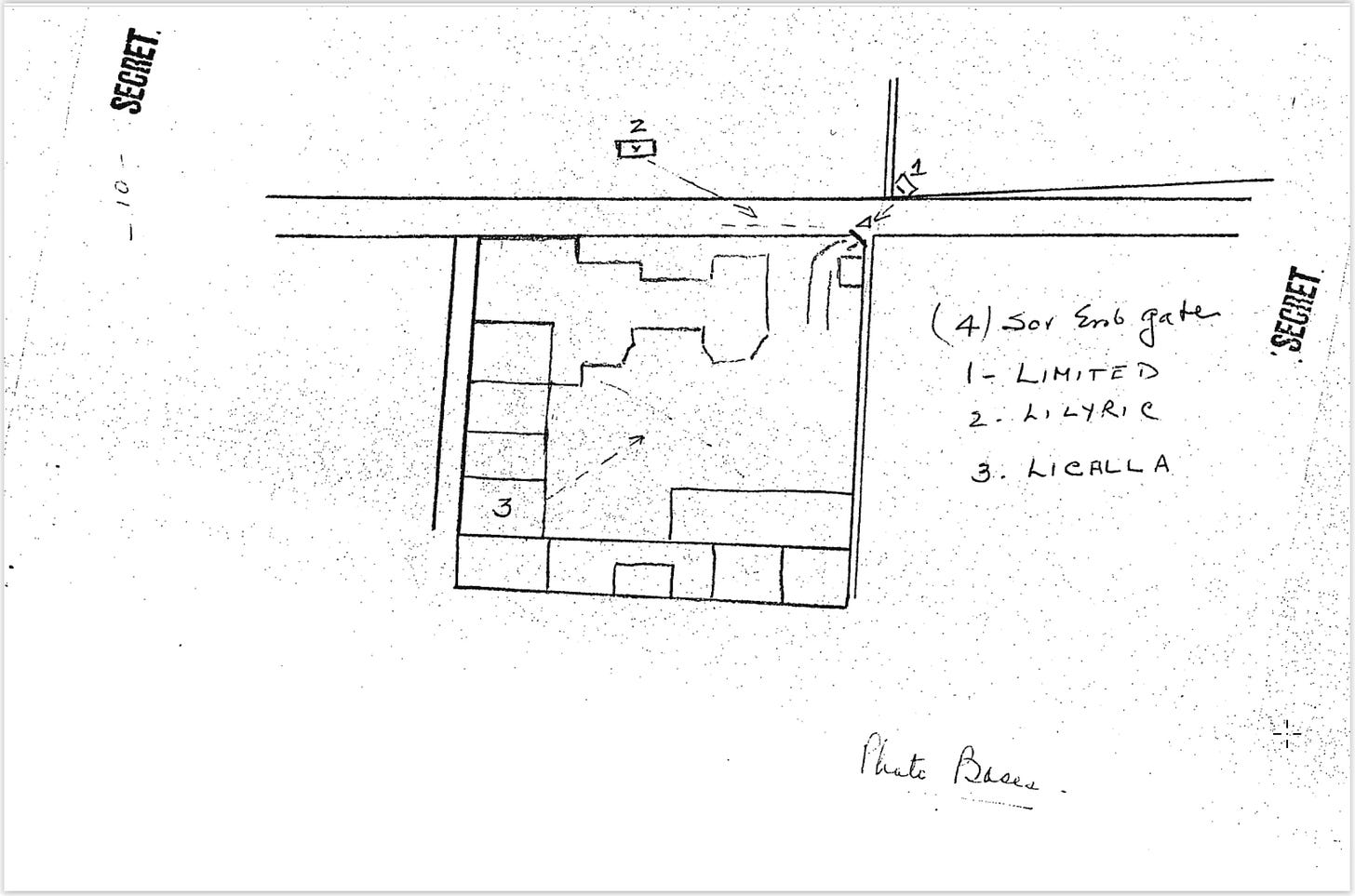

The CIA produced no photos of Oswald entering or leaving the Soviet compound despite heavy photographic surveillance from four sources: three “base houses” in nearby apartments, plus a roving van. It also produced no photos of him entering or leaving the Cuban Embassy, two blocks away, even though he supposedly visited there three times on Friday alone. CIA functionaries claimed — under oath — to have missed him entirely.

This causes many to believe that Oswald was never in Mexico City at all. The official history embodied in the Warren Report portrays Oswald as an impulsive left-wing extremist and homicidally violent Communist sympathizer. Wouldn’t the CIA have wanted to produce photos of him visiting the diplomatic compounds of one or both of the two Communist states to bolster that narrative? After all, the Soviets and Cubans would have denied they did anything but kick the unstable Oswald out of their embassies anyway.

But the CIA still had reasons to withhold or destroy photos. In his introduction to the Mary Ferrell Foundation (MFF) edition of “Oswald, the CIA, and Mexico City,” the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) report by investigators Dan Hardway and Ed Lopez, MFF President Rex Bradford offers three explanations for the CIA’s refusal to supply photo evidence:

Oswald was accompanied by another person and was not a “loner.” …

The person in the photo strongly resembled Lee Harvey Oswald, but close inspection would reveal it was not in fact Oswald.

The photo was taken outside the Cuban Embassy, and the CIA initially hid the photo in order to maintain the fiction that Oswald’s contacts with that Embassy were unknown until after the assassination. (“Oswald, the CIA, and Mexico City,” p. xi)

We can’t dismiss scenario (1) lightly, even if CIA officers who claimed they saw a picture of Oswald said he was alone. The CIA photographic agent(s) would have captured at least two photos — one coming, one going — then handed undeveloped film off to couriers without ever seeing the prints. Plus, we don’t know how many different photos of Oswald the CIA officers actually saw. If he was alone when entering but with a KGB officer as he left, it would have triggered tighter compartmentalization of the photo take.

Scenario (2) might account for the Soviet KGB officers’ accounts of confronting the man eventually accused of murdering JFK and killed by Ruby on Nov. 24, 1963. If the visitor wasn’t that man but closely resembled him, the KGB and G-2 — plus the Cuban Consulate secretary — might have mistaken him weeks later for the man they saw on TV and in newspapers. But the KGB would have treated the doppelgänger like a durak too.

Scenario (3) is also complicated. The “Oswald” who visited the Soviet Embassy didn’t necessarily visit its Cuban counterpart. An impostor may have dealt with the Cubans instead. In fact, the man who would be accused of killing JFK in seven weeks’ time could have been impersonated at both Communist diplomatic compounds. So even if “Oswald” was alone in one or more photos, and the CIA could have shared such “solo pics” with investigators, scenarios (1), (2) and (3) all remain unresolved.

The Cuban Consulate

When Oswald eventually returned to the Cuban compound at around 4 p.m. for his (supposed) third and final visit, the facility was closed to visitors. Employees had stopped admitting visa-seekers at 2 p.m. Supposedly, the Cuban consular officials made an exception for Oswald, who had already appeared twice (at 11:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m.).

The secretary on duty that day, a Mexican named Sylvia Tirado de Duran, had told Oswald earlier that if he wanted to transit Cuba on his way to the U.S.S.R., he had to have a Soviet visa. She said she asked him at 4 p.m. whether he had secured one, and when he said yes but offered no documentation as proof, she called the Soviet Embassy at 4:05 p.m. to verify what he was saying. Twenty minutes later, the Soviets returned her call.

The CIA transcript for this call begins with the Soviet official asking Duran “if the American has been there,” and Duran responding, “yes, he is here now.” The Soviet official explains that the American “wants to go to Russia to stay for a long time with his wife who is Russian,” that “he belongs to an organization in favor of Cuba” and “the Cubans can’t give him a visa without the Russian visa.” He tells her the go-ahead has to come from the Soviet Embassy in Washington, and it would “take 4 to 5 months” in any event.

Duran replies that the Cubans “have to wait also.” The American “knows no one in Cuba,” obtaining a visa “in these conditions” is “difficult,” and he wants to go to Cuba to wait for his Soviet visa, then “leave from there for the USSR.” Then the Soviet official says the American’s wife “is now in Washington,” waiting for a visa to return to the Soviet Union.

Despite the manifest coincidences with Oswald’s life and profile, neither is there mention of Oswald by name, never mind of his appearance, nor of the time he had shown up at the Soviet Embassy. In my opinion, not only were they not talking about the same person, but the whole interaction was part of a successful KGB and G-2 operation to confound, confuse, and ultimately alarm the CIA.

The KGB had received a tip-off and initiated their own little foreign counterintelligence op to upend or derail — in coordination with G-2 — the CIA’s provocation. At the time “Oswald” visited, the newly arrived Cuban consul, Alfredo Mirabal Díaz, was a G-2 officer. The KGB and G-2 were aware both (1) that they were under constant CIA photographic surveillance, and (2) that the CIA was listening to them through bugs and wiretaps. All the interactions therefore constituted a “show” put on for CIA watchers and listeners.

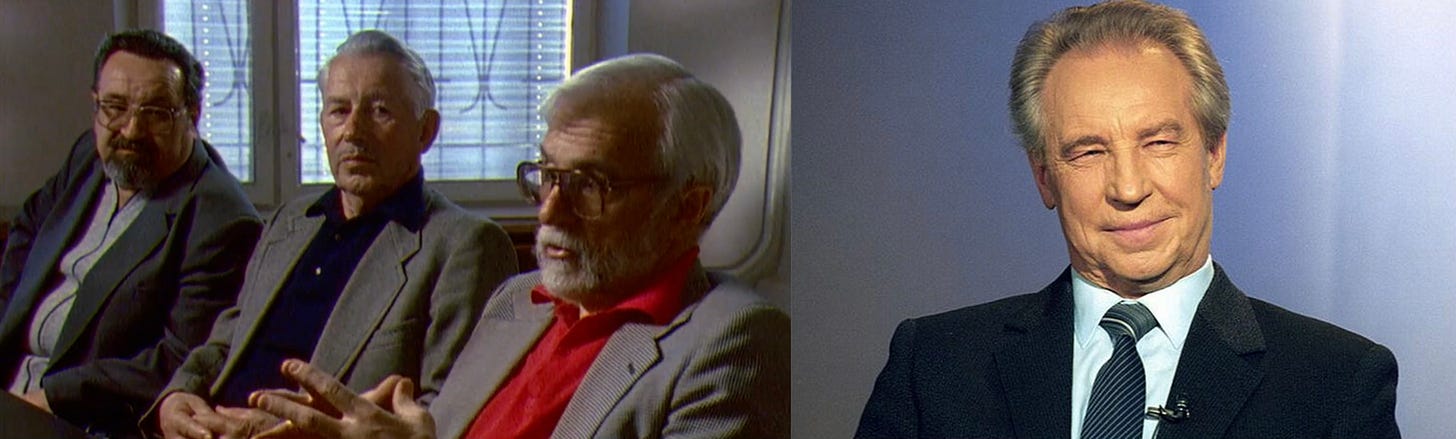

No U.S. government investigators ever interviewed any officials of the Soviet Embassy. Those who interviewed Kostikov, Nechiporenko and Yatskov in 1993 for PBS Frontline’s “Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?” didn’t talk to Obyedkov or the sentry at the gate, and the program aired a week before the National Enquirer published its article about Leonov.

The next installment will show how the three Cuban Consulate employees who claimed to have confronted “Oswald” on Friday, Sep. 27, 1963, conveyed falsehoods to investigators — 15 years after the man accused of killing JFK was murdered in a Dallas basement.

[Part V of the six-part series, “Oswald and the KGB,” can be read here.]

Thanks Chad. Mexico City is the hardest part of all of it. There’s also the angle that Oswald DID go to Mexico City to deliver a bioweapon and was prevented from doing so. Duran is still key as she went through a lot and was still alive at least till a few years ago. One thing is for sure, Mexico was used as sheepdeeping Oswald as Russian Communist and everything had to be covered up and blamed on Oswald as a lone nut to prevent World War III. That was told to LBJ and Earl Warren early on.

Hi everyone. Congrats Chad of course your description is realistic for 99% . But I do live in Ex Russia ans spent my first 35 ys till 1990 under direct KGB rule. When you ask why would a Mexico City KGB know about LHO you have been regressing to the American average level of naiveté. What about a KGB officer being able to read the news in English...LHOs defection and returning were in the news. It was not an everyday case...Later your reporting becomes realistic...sure they wanted to "dangle" the "durak" [ Lenin called them *useful idiots* who believe the lueing dogmas of Marxism on classless society NOT being a slaveowner police state haha ..]