Ukraine's Forgotten Sovereign

As this war reminds us, the past is often so much more interesting than today

Shrill Western supporters of the war in Ukraine object when authoritative commentators and analysts call it a “proxy war,” but that’s what it is. The Ukrainian government isn’t the primary agent of a sovereign nation-state, because Ukraine isn’t one and never has been. It’s a proxy war, grinding to an ugly end.

Amid the monotonous destruction of a distant proxy war, it’s time for an alternate history. That’s a kind of “sci-fi” theme — the basis for more than a few novels, movies and TV shows — but it does break up the tedium. Since the sovereign nation-state feels more and more a nostalgic abstraction with each passing year, why not engage in a bit of reverie?

So, just for the hell of it, here’s an alternate history for Ukraine.

Sovereign Ukraine

Any serious nation-state, even a republic, has at some point had a king. Having once had a king is no guarantee of real sovereignty today, of course, but a country must have had a dynastic monarch at some stage to still be serious today.

The closest thing Ukraine ever had to a king — its last best hope of real sovereignty — was over a century ago. It lasted a few months during the Russian Civil War, and it was replaced by harebrained nationalism, then Soviet socialism.

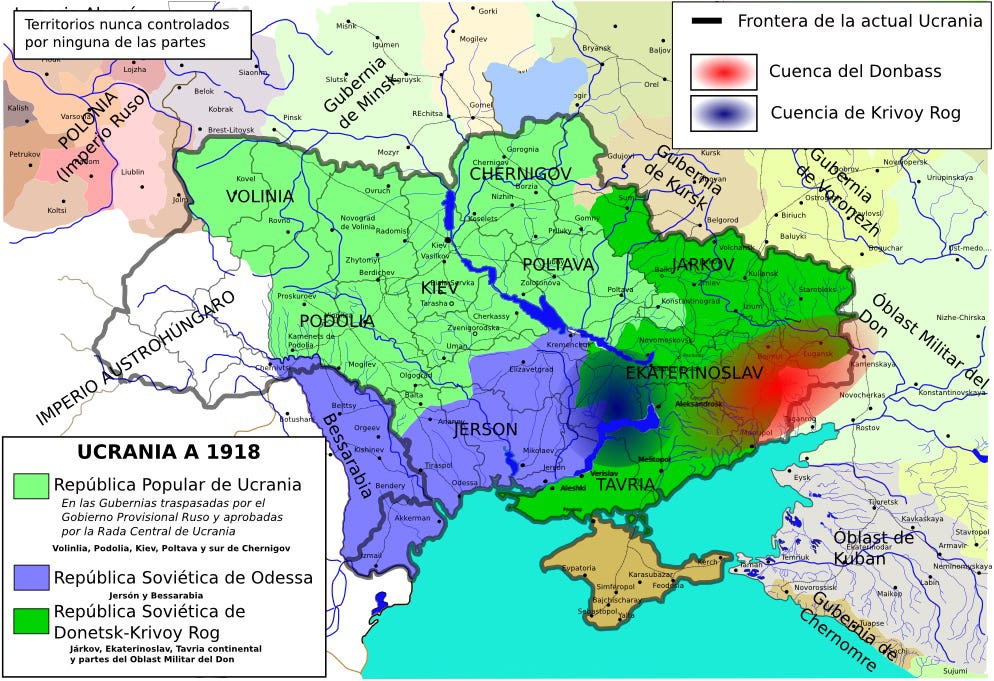

From its inception in 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, until its demise in 1921 at the hands of the Red Army, the nascent “Ukrainian People’s Republic” (UNR) was wracked by war, terror, famine, and other ills. The UNR’s new socialist leaders gave Lenin and his followers every benefit of the doubt as genuine social democrats sincerely seeking peace, prosperity and fraternal co-existence with them.

The socialists didn’t even seek statehood, only greater autonomy within a loose, Russia-centered union. They disbanded their most capable armed units and dismissed their best military leaders, believing a true socialist democracy didn’t need any of those.

The violence unleashed on Ukraine from all sides quickly destabilized its budding socialist government until, for seven months in 1918, Ukraine became a monarchy.

Called the Hetmanate, it was headed by Pavlo Skoropadsky — a former general of the Russian imperial army and a descendant of 18th-century “hetman” Ivan Skoropadsky.

Having fought in both the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 and WWI, Skoropadsky was a highly decorated, able commander. Ukraine’s socialist government dissolved the army corps under his command, but in April 1918, a “Congress of Agrarians” elected Skoropadsky “Hetman of Ukraine.” He dissolved the fractious, do-nothing Central Council (legislature) and made the “State Guard” the chief organ of government.

The great Russian satirical (and mad) writer Mikhail Bulgakov, author of “The Heart of a Dog” (1925) and “The Master and Margarita” (1938), based a lesser work, “The White Guard” (1925), on the Hetmanate interregnum, poking fun at it. But Skoropadsky enacted real reforms in his short tenure. Had he consolidated his vision, Ukraine today would be a very different place. It’s hard, at any rate, to imagine it turning out any worse than it did.

Ukrainian nationalists despised Skoropadsky, in spite of his refusal to unite with Soviet Russia or tolerate movements sympathetic to the overthrown Russian tsar on Ukrainian territory. (The Bolsheviks executed the Russian royal family a few months into Skoropadsky’s reign anyway.) But the Ukrainian nationalists (the word “socialist” often included in their parties’ names) eventually teamed up with the Ukrainian socialists.

Those socialists made little effort to conceal their financial support from Moscow. As they happily declared their neutrality toward Soviet Russia — and their hostility toward the Hetmanate — they plotted to take power back.

When the Central Powers in WWI surrendered in November 1918, the “Entente” or Allied Powers (Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and U.S.) acted on behalf of their deposed erstwhile ally, Tsarist Russia, in refusing to recognize the Hetmanate as independent.

The “Volunteer Army” of Gen. Anton Denikin, a leader of the “Whites” in the Russian Civil War, categorically rejected any notion of a new state — however benign — anywhere on the Russian Empire’s old territory. Since Denikin no longer spoke for a government in power, it was extraordinary that the Allies were so ready to do his bidding. But they did.

The Hetmanate had not, incidentally, drawn on a legacy of independent Ukrainian nation-statehood (there was none), even though its leadership hoped for independence in 1918. The Hetmanate that existed for two and a half centuries from the mid-16th to the late 18th centuries had been a kind of “duchy,” first of Poland, then of Muscovy and Russia. It was a “quasi-monarchical” non-sovereign state except for about four years in the 1600s. So the Hetmanate was a “quasi-restoration” of monarchy. Strange, but authentic.

Any kind of restoration of monarchy is very rare in history, however, and the West simply rejected this authentic Ukrainian entity. In other words, we sold them out. Skoropadsky abdicated in December 1918, and the UNR fought on haplessly until the Bolsheviks took over and terrorized the place in their own, inimitable way.

The experiment in modern Ukrainian monarchy failed at a time when socialism was “all the rage,” and the true nature of the Bolshevik government was mostly unknown to the outside world. The subsequent horrors in Ukraine are now infamous in modern history. One contemporary American historian describes Ukraine as part of the “Bloodlands” of Eastern Europe, alternately ravaged by the Third Reich and the USSR.

Skoropadsky, the “Last Hetman of Ukraine,” perished in exile in Germany in 1945. Having refused to cooperate with the Nazis, he was killed in a WWII bombing raid.

The term “Ukraine” never applied to any formal nation-state until the 20th century and never secured worldwide recognition until that century’s final decade, when the U.S.S.R. disintegrated. But it was the Soviet Union that created Ukraine’s international borders. The current-day Ukrainian ultranationalists that came to power after the coup in February 2014, sparking war, do not resonate in history. They are, to put it bluntly, “ersatz.”

Nevertheless, Washington — as it so often has — backed the ersatz political model, Ukrainian ultranationalism, with its neo-Nazi symbology and glorification of Nazi-allied WWII figures. Massive death and destruction were bound to ensue. All Russian President Vladimir Putin needed was an excuse to invade, and we gave him one.

Ukraine is now bogged down in an unwinnable proxy war against hoodlum Putin’s Russia, a war in which no one in the entire West has defined a clear strategic objective, and in which no American has ever identified a vital U.S. national interest at stake. This is what U.S. nation-building looks like today.

Following is an English translation of an article published in 2012 by a Ukrainian author, offering an unorthodox perspective on the Hetmanate of 1918. I publish it here only to give readers an idea of how little attention American policymakers ever pay to history and culture in launching foreign military interventions and nation-building in the 21st century. The idea of a sovereign Ukraine is set to be on the Losing Side of History once again.

The author creates the impression of a sovereign with popular support who attracted contempt from almost every sector of the political elite, which was highly unsavory across the spectrum. All but a small coterie of loyalists were arrayed against him, as the leaders of all parties claimed to act on behalf of “the people.” The Hetman meant well, and for that he had to lose. That much in this story should be familiar to any honest political observer.

Herewith, another example of “what might have been” over a century ago.

Hetman Skoropadsky’s “Operation Federation with Russia"

by Dmytro Kalynchuk (first published in Tyzhden ~ 15 November 2012)

Perhaps no leader in the history of Ukraine has been subjected to as much slander and humiliation as the Hetman of the Ukrainian State, Pavlo Skoropadsky. In what is — probably — a unique case, Hetman Pavlo was hated by almost all of his contemporaries.

For the socialists, he was the tsar’s general and “squire.” For fans of the Russian Empire, he was a traitor and separatist. For the Bolsheviks, he was the general who stopped the Reds’ advance into Kyiv in November 1917 — and a class enemy. And most tragic of all, for Ukrainian patriots, he was a German puppet and White Guard sycophant. However, a detailed study of the period of the Hetmanate leads to very different conclusions.

Wrongfully Accused

The Hetman was criticized for surrounding himself exclusively with supporters of the “single and indivisible” Russia. Not true. The Hetman’s administration included such well-known Ukrainian patriots as Vyacheslav Lypynsky, Sergey Shelukhyn, Dmytro Doroshenko, Mikhaylo Chubynsky (son of the author of the national anthem, “Ukraine Is Not Yet Dead”), future Ukrainian nationalist ideologue Dmytro Dontsov, and many others.

Mykola Mykhnovsky was invited to become a personal adviser to the Hetman, but the ideologist of Ukrainian independence wouldn’t accept a post lower than minister.

Naturally, many former tsarist officials worked in the Ukrainian state apparatus, just as in the days of the Directorate.1 Generals Galkin, Grekov, Sinkler and Yunakov were former tsarist generals: they didn’t speak the Ukrainian language, but this didn’t stop them from holding senior positions in the army of the UNR.2

The Hetman was also criticized for the fact that, under his power, local authorities accepted many people who were openly hostile to Ukrainian identity. This was certainly the case. Distinguishing themselves as particularly odious were Kyiv Province Mayor Chartoryzhsky and Kharkiv Province Mayor Zalessky, who referred to Ukrainians as “Mazepites”3 and the Ukrainian language as an “unnecessary innovation.” But it wasn’t the Directorate of the UNR that dismissed these characters from their posts. It was the administration of the Hetmanate — and precisely for “Ukrainophobia.”

The same goes for the death squads created by landowners to terrorize the peasants, and facilitated by the German command. These units were eliminated not by the rebels of Atamans Angel or Green,4 but by the security centurions of the State Guard, by order of the Hetmanate’s Minister of Internal Affairs, Ihor Kistyakivsky.

Nor is it true that the period of the Hetmanate represented the continuous robbery of Ukraine by German troops. “Life in Yekaterinoslav5 was in full swing… After the Soviet famine, there was a sharp drop in prices for food, and there were huge quantities of food products at the markets,” recalled Professor G. Igrenev.

The Hetmanate’s tenure in power actually represented a period of Ukrainian industrial revival after the devastating Bolshevik invasion. One coal mine alone increased its production 1.5 times (from 30 to 50 million poods6 per month) during the time of the Central Council. Ukraine traded sugar, canned meat, butter, sunflower oil, etc., with Germany and Austria.

Accusing the Hetman of all kinds of mortal sins, the UNR Directorate actually took full advantage of the Hetmanate’s economic achievements. “The impression was created of a dozen hands grasping at the Hetmanate’s treasures,” recalled a staff officer of the UNR’s Zaporizhia Army Corps, the centurion Avramenko, during the first days of the Directorate’s rule.

There is one charge that won’t wash off though, and that is the “Charter on the Federation of Ukraine with Russia.” With this document, Hetman Skoropadsky — it seems — forever renounced the idea of Ukraine’s independence and demonstrated his commitment to the “single and indivisible.”7 But it wasn’t all so simple.

The Entente’s Verdict

Critics of Pavlo Skoropadsky usually sidestep the fact that the Entente was making demands on the Hetmanate to unify Ukraine with Russia. After Germany lost WWI, the Entente became master of the situation. For the Entente, Ukraine was nothing but a German puppet regime. The countries of the Entente had a number of agreements with the government of Tsarist Russia. Acting on its behalf in the fall of 1918 was the Volunteer Army of General Anton Denikin, for whom “there is not, never has been, and never will be” any Ukraine. The Entente countries did not want to support separatist movements that had arisen on the territory of its ally state — under any circumstances.

It is thus possible to consider Ukrainian diplomacy a success for the fact that the Entente’s representatives generally held talks with the envoys of the Hetmanate (they ignored the Directorate). However, they were prepared to recognize Ukraine only as a part of Russia. In any other circumstance, Ukraine would become for the Western states an ally of Germany, against which they would have waged war in alliance with the Volunteer Army. Ukraine could not oppose them, as it hadn't yet managed to create its own army.

The Bolshevik threat also demanded agreement with the Allies. At the 6th Congress of Soviets, Leon Trotsky openly declared his intention to seize Ukraine the moment German troops left its territory. One very pragmatic factor convinced the Bolsheviks to carry out the seizure of Ukrainian lands: Ukraine had the harvest of 1918 in its hands, and Red Russia was dying of hunger. Only the forces of the Entente could give Ukraine time to deploy its own army.

But the Allies did not intend to restore the Russian Empire within its former borders either. That is why they did not demand that the Hetman eliminate Ukraine as a state entity, only that it unify with Russia to one degree or another. In fact, the Allies demanded that Ukraine revert to the state of affairs at the time of Hetman Khmelnytsky, when Ukraine entered into the body of Russia, with its own government, army and judicial system.8 No one was offering Hetman Skoropadsky any other choice.

Federation with the Martians

Another fact that persistently evades critics of the Hetmanate is that the Hetman announced the Charter of Federation with a state that did not exist at the time. The only country going by the name “Russia” in November 1918 was the Bolshevik republic, and Hetman Skoropadsky was — naturally — not going to unite with that.

In November 1918, there were the self-declared states of the Ufa Directorate, the Great Army of the Don, and the People’s Republic of the Kuban on the territory of the former Russian Empire. None of them were Russia. Hetman Skoropadsky could have proclaimed a union with Mars or Venus with the same degree of success.

The 35,000-strong Volunteer Army of General Denikin didn’t control a single territory at that time, and was located on the territory of the Don by agreement with the Don government. That is why the “Charter of Federation” contains these words regarding Ukraine: “She is the first to appear in the matter of the All-Russian Federation, the ultimate goal of which will be the restoration of Great Russia.”

The man whom the “Charter of Federation” had the power to make insanely angry was Gen. Anton Denikin. “Never, of course, will any kind of Russia — reactionary or democratic, republican or authoritarian — fail to repudiate Ukraine.” Thus, he expressed his attitude to the Ukrainian question, clearly and succinctly. In the constitution of the Russian Empire, Ukraine had no autonomy. The command of the Volunteer Army saw no reason to somehow change this state of affairs in the future.

At the same time, nowhere in the “Charter of Federation” is there any mention of the Hetman’s renunciation of power, or of the liquidation of Ukraine as a state entity. “The Hetman issued a message under the auspices of Russia on federative principles, by which Ukraine retains her sovereignty,” wrote the ambassador of Ukraine in Berlin, Baron Fedir Shteingel, to former Foreign Minister Dmytro Doroshenko.

Because of the “Instrument of Federation,” the command of the Volunteer Army found itself in a very interesting position. On the one hand, the Volunteers themselves were barefoot, hungry, and too weak to resist the Bolsheviks. What awaited them was a long and exhausting war with a force that controlled the entire central part of Russia, followed by the no-less-arduous process of raising the country out of the ruins. They could not imagine how Russia’s political future would look. It had to be decided by the Constituent Assembly, the delegates of which had yet to be elected in a country where large numbers of people were under the rule of the Reds.

However, with the proclamation of the “Charter of Federation,” Gen. Denikin was forced to put up with Ukraine as a reality. Ukraine became legitimate in the eyes of the Entente, and, moreover, the Hetman already controlled territory on which no civil war was going on, where industry worked and a sovereign foreign policy existed.

The Volunteers had yet to create all this. Even with Don and Kuban, they had still to explain themselves somehow. In these circumstances, the likelihood that Ukraine would really become an enslaved part of Russia was almost zero.

The Hetman’s Multivector

The situation inside the country negated the Hetmanate’s foreign policy successes. The diary of Dmytro Dontsov describes repeated criticisms of the Hetman for the fact that he was forced to build Ukraine “in spite of the Ukrainians.” Almost from the first day of his power, the Hetman had to overcome resistance from Ukrainian society. The socialists of the Central Council hated the Hetman and flatly refused to cooperate with him.

“Svetozar Drahomanov (a bureaucrat in one of the ministries of the Central Council) came to my chief, Vice-Minister of Internal Affairs Vyshnevsky, to announce his resignation, not wanting to remain in the ‘anti-Ukrainian government of the Hetman.’ At this stage, Vyshnevsky spoke in Ukrainian, and Drahomanov in Russian,” recalled Dontsov.

Refusing to work in the government, the socialists were actively subverting the state, not disdaining cooperation even with the Bolsheviks. Vynnychenko didn’t hide the fact that even Red Moscow had allocated money to the socialists to overthrow the Hetman.

“Negotiations with Manuilsky were based on the following: to achieve the neutrality of the Bolsheviks in our war against the Hetmanate. We had absolutely no hostile intent toward Soviet Russia,” admitted Ukrainian National Union Chairman Mikita Shapoval. This was after the Battle of Kruty and the Kyiv massacre...9

The State Guard (Police ‘A’) and the Special Department of the Staff of the Hetman (political intelligence) were aware of these activities and prevented them by all means. As a result, the State Guard arrested many of the socialist leaders. Without batting an eyelid, the socialists portrayed these facts as repression against politically conscious Ukrainians.

On the one hand, the Hetman was under the pressure of the socialists’ destructive activity; on the other, he needed lots of experienced managers. He had to choose people from among the many tsarist officials in the country. Plus, a huge number of businessmen, entrepreneurs and military personnel had fled from Bolshevism-plagued Russia.

Even though all these people were very skeptical about the very existence of Ukraine, the Hetman nevertheless decided to use their talents as long as cadres of experienced managers and entrepreneurs had not yet emerged from among native Ukrainians. Naturally, for this Pavlo Skoropadsky had to make concessions on the cultural question — to de facto recognize the equal legal status of the Russian and Ukrainian languages.

The issue of school education, for example, was entrusted to local government bodies — the zemstvos. Hence, where most of the population (and thus — most of the zemstvo deputies) consisted of Russians (and this was all the major cities), the Ukrainianization of education almost did not happen. As a consequence, accusations were directed at the Hetman such as: “He brought the ‘single and indivisibles’ to power,” and “They are building Russia in Ukraine.” These accusations were groundless. It was precisely under Hetman Skoropadsky that two Ukrainian universities appeared (in Kyiv and in Kamianets-Podilsky), about 150 lyceums were established, and the Academy of Sciences was created. Accusations of electoral repression against Ukrainians were also unfounded.

The right-wing pro-Russian organizations were harassed under the Hetmanate at least as much as the Ukrainian socialists were. On July 7th, 1918, the State Guard dispersed a monarchist demonstration in Kyiv. Noteworthy is also the decree of the Hetmanate’s Ministry of Internal Affairs: “At the request of visitors, orchestras are playing monarchist Russian songs… while this is happening, those in attendance are listening and standing to salute... I decree: 1. Arrest the participants in these demonstrations and send them to Russia, so that they can salute officially there and not display their devotion to their cherished political ideas in restaurants and on promenades.”

Devotional Understanding

Hetman Skoropadsky did try to talk to the Ukrainian socialists. On October 17th, 1918, when it became clear that Germany’s defeat in the war was only a matter of time, the Hetman declared a charter in which he expressed his intention to “stand on the soil of an independent Ukrainian state.” On October 25th, five ministers were accepted into the government — Ukrainian National Union representatives Andriy Vyazlov, Olexander Lototsky, Petro Stebnytsky, Mykola Slavynsky (all from the Party of Socialists-Federalists) and Volodymyr Leontovych (non-partisan).

At the same time, Hetman Skoropadsky made an unprecedented compromise: the hated Ukrainian National Assembly power-ministers Ihor Kistyakivsky (Internal Affairs) and Borys Stelletsky (chief of the Hetman’s staff, which in particular controlled the Special Department) were fired. Both were extremely talented organizers, and removing them from their positions of course affected the quality of information that the Hetman received.

Yet the leaders of the socialists did not want mutual understanding. Already in September 1918 they were preparing an uprising against the Hetman. The latter was implemented as an initiative of the National Union, but in fact, behind it stood exclusively the leaders of the socialists and the command of military units of the Hetman’s army: Sich Riflemen, Black Sea Kosha, Zaporizhia divisions, the Railway Corps and the Podilsky Corps. “The National Union is not thinking about an armed struggle at all,” lamented Mykyta Shapoval.

Nevertheless, the intention was proclaimed on behalf of the National Union to gather the National Congress on November 17th in order to determine the future system of government in Ukraine. In fact, Vynnychenko and Shapoval were preparing a cancellation of the Hetmanate by the Congress.

How did the Hetman view the prospect of his personal participation in this Congress?

"It was either that or try to become the head of the Ukrainian movement myself, trying to seize everything into my own hands. The implementation was depicted in such a way that I myself announced the Congress and changed the composition of its members, filling it with members from only left-wing parties," recounted Pavlo Skoropadsky.

However, on November 13th officers of the Special Department of the Staff of the Hetman arrested his chief of security, Colonel Arkas. Counter-intelligence agents learned from him that the rebels were already prepared to revolt, and that it was going to happen regardless of the decisions of the Congress. The same day, the leaders of the socialists and the rebel generals formed the Directorate and decided to begin the uprising. At that moment, there was still no “Instrument of Federation.”

Pavlo Skoropadsky was in a desperate situation. Going with the flow meant giving power to the socialists — i.e., to the people who had already brought Bolshevik occupation to the country. The Hetman was convinced that in the event of the socialists coming to power, the Bolsheviks would quickly gain control of Kyiv — and he was not mistaken. It was as though, to save Ukraine from enemy invasion, he had to go against the will of the Ukrainian people. And to the Hetman this was not the first time for building Ukraine “in spite of the Ukrainians.”

The Hetman’s officials decided to go for broke and rely on the “Special Corps” — a military unit made up of pro-Russian officers, who in the future would have to be transferred to the front to Denikin (thus ridding Ukraine of these odious cadres).

Unfortunately, in order to rely on the pro-Russian forces, it was necessary to declare the restoration of the “single and indivisible.” It was then, on November 14th, that the “Charter of Federation” appeared, a document that had been pressed on the Hetman by the Allies. “In Ukraine, the federation will take one of the first places because from it stems the order and legality of the territory,” noted the Charter.

The Hetman grossly miscalculated in assessing the balance of power. After the Charter, even the Ukrainian parties that were his allies — agrarian-democrats and socialist-federalists — turned their backs on him. For the whole country, Pavlo Skoropadsky became a traitor. The Hetmanate’s officials still hoped that the rebels and “single and indivisibles” would exhaust each other, and that the Hetman could emerge above the fray (actually, because of this, the Hetman did not lead the army to suppress the rebels himself). Yet these hopes were not realized.

At the critical moment, partisans of the “single and indivisible” — previously very noisy at rallies and in newspaper columns — avoided en masse the mobilization to officer formations. General Keller, appointed commander of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, was such a fierce Ukrainophobe that even the Hetman’s Cossacks and ideological Hetmanate officers started going over to the side of the Directorate.

Hope for support from the Entente turned out to be in vain as well. The German units that were still stationed in Ukraine at the time carried out all the orders of “the countries of the agreement.” The arrival in Kyiv of representatives of France (who were already in Odessa) would have been enough for the Germans to cease all negotiations with the Directorate and force the rebels to sit at the negotiating table with the Hetman. But the Entente representatives did not arrive in Kyiv. The Hetman had lost, and was forced to abdicate.

We should not exaggerate the role of the Hetman in all these events. Already within six months, Chief Ataman Petliura had presented the White Army command with the draft bill on Ukraine’s entry into Russia on a federative basis. But the conditions in which Petliura found himself then could not be compared with those of the Hetman. The Entente did not recognize the UNR and refused to speak with the representatives of the Directorate.

Denikin had not the slightest desire to go to any negotiations with the “separatist Petliura.” The Ukrainian army was doomed to war on three fronts and further internment. The Bolsheviks implemented the final plan on the autonomous status of Ukraine as a constituent part of the renewed Empire. Ukraine paid for such autonomy with the Holodomor [the state-imposed famine in Ukraine from 1932-33 ~ Ed.] and the delights of Stalin’s GULAG.

“The Charter of the Federation of Ukraine and Russia” was evaluated differently even by its contemporaries. The head of the Ukrainian Hetmanate’s telegraph agency, Dmytro Dontsov, considered it a betrayal: “That the Charter proclaimed a federation with a defunct Russia does not justify it. Questions of state independence are not a matter of tactics, but principles.”

At the same time, the former chairman of the Sich Riflemen, Osyp Nazaruk, who had personally put a reference to the “Federative Charter” in the declaration of the Directorate, as an émigré sincerely repented his participation in the rebellion against the Hetman. He did not consider the “Charter of Federation” to be a betrayal “because Skoropadsky accustomed Moscow to Ukraine, not Ukraine in Moscow.”

The name of the Ukrainian social-democratic government led by Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Symon Petliura

Ukrainian People’s Republic – the social-democratic republic that existed before and after the Hetmanate

Followers of 18th-century Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa, who betrayed Peter the Great by allying with Sweden against Russia

The Atamans — or ‘Commanders’ — Yevhen Angel and Danylo Terpylo (widely known as the “Green Ataman”), led rebellions against the Bolsheviks and on the territory of the former Russian Empire in 1918-19.

The city of Yekaterinoslav was renamed Dnepropetrovsk in 1926, a combination of the River Dnieper, which the city straddles, and Grigory Petrovsky, a local Bolshevik leader. It was renamed Dnipro in 2016 by the pro-Western Ukrainian government.

A pood is a unit of weight measurement equal to about 1.38 kg.

Adherents to the Russian imperialist concept of a “single and indivisible” Russian Empire

Bohdan Khmelnytsky was Hetman of the Zaporizhian Host of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He led an uprising against the Polish Crown in 1648 and created a Ukrainian Cossack state in 1651. In 1654, having considered an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, Khmelnytsky entered into a treaty with Moscow to secure the protection of the Russian Tsar for his Orthodox Christian state. There followed a period in Ukrainian history known as “The Ruin,” when Ukraine was torn apart by war, internal political rivalries, and Russian subversion. Poland and Russia partitioned it in 1667.

The Battle of Kruty took place in January 1918 between a force of Ukrainian “Free Cossacks” and military academy cadets and troops of the Bolshevik Red Army, in which the Ukrainian force was outnumbered about ten to one. Although the Bolshevik forces lost more men, they ultimately overran the resistors, executing those taken prisoner. The same month, about a hundred Jews were killed in clashes between Ukrainian nationalist and Bolshevik forces.