Oswald and the KGB — Part VI

How the Soviets and Cubans thwarted a CIA provocation in Mexico City

What happened in Mexico City when Lee Harvey Oswald supposedly visited remains a mystery, and it still will at the conclusion of this, the final installment in this series. But certain facts — against the backdrop of voluminous literature — give rise to strong intuition. That’s what’s offered here.

What Happened

At around 11 a.m. on Friday, Sep. 27, the man who would be shot to death in Dallas police custody by Jack Ruby on Nov. 24, 1963 (or, in a surreal scenario, someone who bore an uncanny resemblance to him and carried his ID), showed up at the Cuban Consulate in Mexico City to ask what he needed to do to if he wanted to stop off in Cuba on his way to the U.S.S.R. Secretary Sylvia Tirado Duran hardly looked up at Oswald during this brief encounter. She just told him he needed a Soviet visa and four passport-size photos to apply to transit Cuba and identified a place where he could get them nearby.

At 12:30 p.m., Oswald appeared at the Soviet Embassy’s front gate. He really did want to return to the U.S.S.R., the best memory of his short life, to live there with his young family for good. He told the undercover KGB officers that and said he’d hoped to go there via Cuba, a place he’d never been, but that the Cubans said he needed a Soviet visa first.

These consular officials told Oswald that normally he’d have to wait at least four months for a Soviet visa, and that he’d have to receive it in the United States, not Mexico. The mounting realization that things weren’t going to work out the way he’d hoped made Oswald increasingly dejected and anxious. He’d planned to leave for Havana on Monday, Sep. 30, but that seemed impossible now. When he finally started to become visibly upset, teary-eyed and frantic, the KGB officers sought to reassure him.

Maybe, they said in soothing tones, they could swing an exception for him, just this once. If he left his passport and other documents with them, they’d try to arrange his Cuban transit visa. If their Cuban allies agreed, his Soviet visa would be in the bag. They told him to check back the next morning to see if they’d had any success. Eager to believe them, Oswald consented to the Russians’ ad hoc proposal, thanked them, and sauntered off.

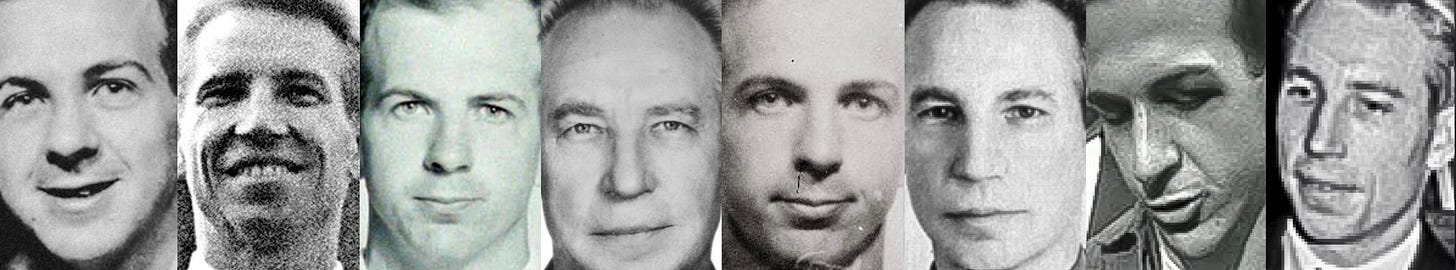

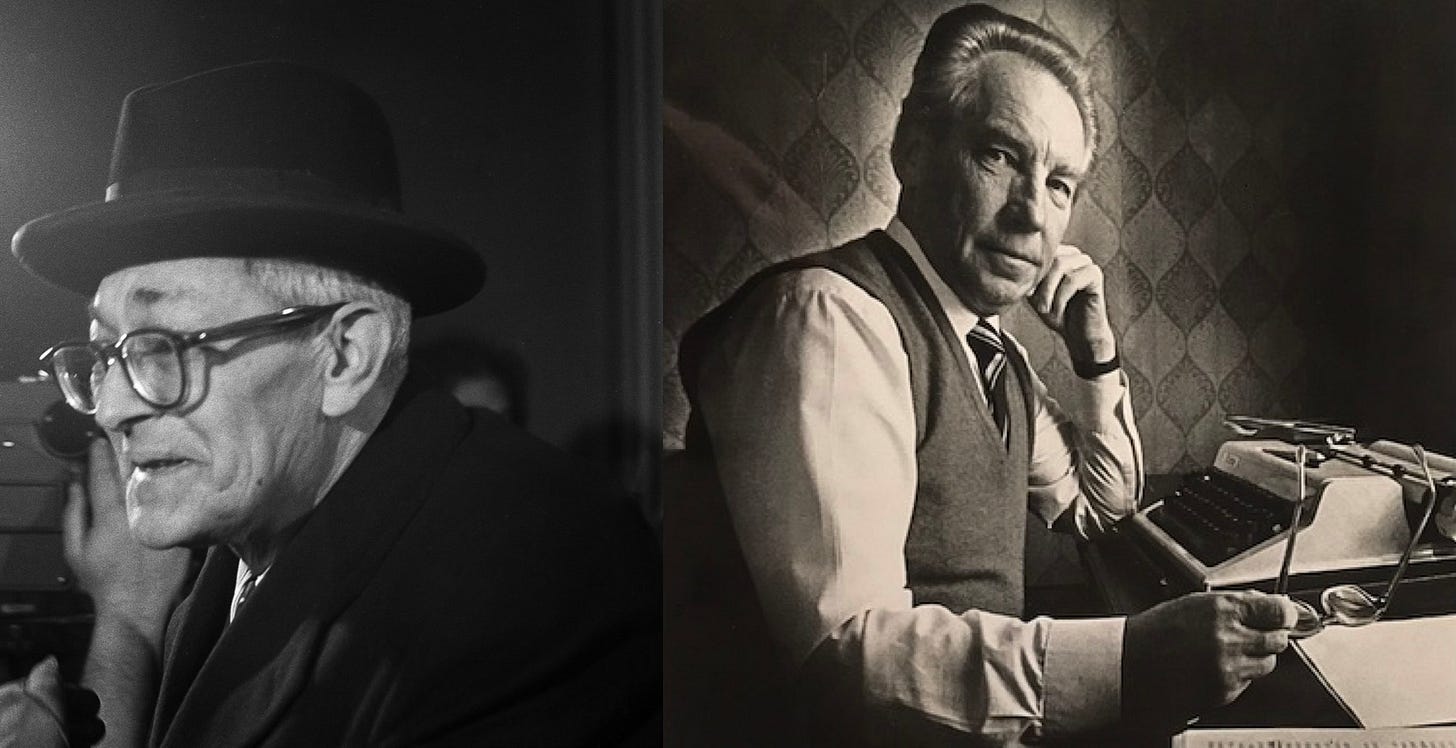

The KGB had already settled on Nikolai Leonov to impersonate the American. True, he wasn’t a dead ringer. Leonov was 35, considerably shorter, and blond. But with a little henna or other temporary coloring, he could darken his eyebrows and tint his very fair hair, receding slightly at the front, and pass himself off as Oswald in the Cuban Embassy.

His training in the KGB’s First Chief Directorate would serve him well. Thanks to plenty of KGB surveillance of Oswald inside the U.S.S.R. — along with the American’s more recent appearances on TV in New Orleans — Leonov had taken a crash course in looking and acting like the young ex-defector. His English was good enough for him to pose as an American in front of any native Spanish speakers who weren’t in on the plot.

The Russian spy entered the Cuban Embassy compound at about 1 p.m. and presented Oswald’s voluminous documentation. He told Sylvia his pro-Communist and pro-Cuban materials proved he was a “friend.” She thought this rather strange but repeated that he would have to get a Soviet visa first. She could type up his Cuban application and staple the photos to it, but he’d still need that visa to the U.S.S.R. or he wasn’t going to Havana.

Leonov came back at 4 p.m. to tell Sylvia the Soviets had agreed to give him the visa, forcing her to call their embassy to check up. After she put the phone down and confronted him, Leonov got his chance to shine as an impostor. He yelled, cried, and made a spectacle of himself as mentally unhinged and emotionally imbalanced. Eventually, Eusebio Azcué angrily ordered him to leave and never come back.

The next morning, the American Oswald showed up quietly at the Soviet Embassy, and a KGB officer met him at the gate. Oswald might even have received his passport and documents through the bars, since the Russians didn’t need to let him inside to deliver the simple message: sorry, no deal. It was likely over in seconds. The only place the young ex-defector to the U.S.S.R was going from Mexico was back to Texas.

The CIA’s Reaction

Leonov had made such a racket inside the Cuban Consulate the day before that if an actual CIA employee didn’t hear it, one of the Cuban Embassy officials that the CIA had already recruited surely did. At least one would have reported back to the station about the “Oswald” encounter, which was so loud that passers-by could hear it out in the street.

The CIA became alarmed. That wasn’t their boy in there making a scene. It was someone else, and by now they knew they were no longer in control of the Oswald provocation. But then something else happened to rattle the CIA even more. At 11:51 a.m. the next day, Saturday, Sep. 28, the CIA intercepted a phone call to the Soviet Embassy.

The transcript reads:

WO while waiting speaks in English to someone in the background: He said wait … Do you speak Russian? Yes. Why don’t you talk to him? … I don’t know … /MO takes the phone and says in broken Russian/ I was in your embassy and spoke to your consul. Just a minute. MI takes the phone and asks MO in English what does he want?

MO: /in Russian/ Please speak Russian.

MI: What else do you want?

MO: I was just now at your embassy and they took my address.

MI: I know that.

MO: /speaks terrible, hardly recognizable Russian/ I did not know it then. I went to the Cuban Embassy to ask them for my address, because they have it …

MI: Why don’t you come again and leave your address with us, it not far from the Cuban Embassy.

MO: Well, I’ll be there right away.

“WO” means “Woman Outside,” meaning the female voice on the phone that was calling into the Soviet Embassy. “MO” (Man Outside) was the male voice that she put on the phone, and “MI” (Man Inside) was the Soviet Embassy official receiving the call.

The CIA’s husband-and-wife team transcribing tape recordings of intercepted phone calls to and from the Soviet Embassy were Boris and Anna Tarasoff. Boris was a native Russian speaker who knew Spanish; Anna a native English speaker who knew Russian. When testifying to the HSCA in November 1976 and April 1978, Boris and Anna conveyed the “special” nature of “Oswald” at the time of his supposed visit to Mexico.

When Boris transcribed the tape of the Saturday conversation, he had no idea who the “Man Outside” was and had never heard his voice before. Yet after that call, the CIA pressed him to urgently identify the caller. Boris thought it might be because “sometimes” a “so-called ‘defector’ from the United States” contacted the Soviet Embassy in an attempt to go to Russia, and “we had to keep an eye on them,” he explained to Congress.

Boris: Consequently they were very hot about the whole thing. They said, ‘If you can get the name, rush it over immediately.’

Boris imagined — reasonably — that this was what had caused the CIA’s panic. But he was only guessing, and he was wrong. Speculating fifteen years later, he still didn’t know why the CIA was so “hot” about learning the identity of the caller and even admitted he had “no idea” what had led to the urgent request. He just followed orders “to find the name, to get the name of this person and deliver it as soon as possible to the station.”

Finally, on a call intercepted on Tuesday, Oct. 1, Boris heard a voice that was the same as the “Man Outside” on the Saturday call. This time, he said his name was “Lee Oswald.”

The transcript of that call reads:

MO /the same person who phoned a day or so ago and spoke in broken Russian/ speaks to OBYEDKOV.

MO: Hello, this is LEE OSWALD (phon) speaking. I was at your place last Saturday and spoke to a consul, and they said that they’d send a telegram to Washington, so I wanted to find out if you have anything new? But I don’t remember the name of that consul.

OBY: KOSTIKOV. He is dark /hair or skin?/.

LEE: Yes. My name is OSWALD.

OBY: Just a minute I’ll find out. They say that they haven’t received anything yet.

LEE: Have they done anything?

OBY: Yes. They say that a request has been sent out, but nothing has been received as yet.

LEE: And what … ? /OBY hangs up/.

Boris testified that he “very seldom” underlined the name and usually only “put them in capitals” for his CIA superiors. In this case, he underlined it “because it was so important to them.” But the transcript isn’t entirely Boris’s handiwork anyway. It says “previously transcribed” and names Obyedkov, the Soviet Embassy’s security chief, as the person “Oswald” was speaking to. Boris didn’t write that. By his own admission, he never established who the person on the other end of the line was, and he was familiar with the voices of the English-speaking Russians in that embassy. An interview in Guadalajara on Nov. 29, 1976, features this exchange with HSCA investigator Kenneth Brooten:

Brooten: Did you ever learn, in the course of your subsequent translation of telephone intercepts, the identity of the person that Oswald was talking to?

Boris: No, unfortunately not. I couldn’t place him.

This means someone else typed up this version, no doubt at the CIA station. As noted, Ivan Obyedkov had no memory of such a call on that day, and Nechiporenko said the embassy received no outside calls on Saturday either. We can believe the CIA falsified transcripts as well, because they concealed at least one. Anna Tarasoff testified to the HSCA on Apr. 12, 1978, that she remembered another transcript involving “Oswald”:

Anna: According to my recollection, I, myself, have made a transcript, an English transcript, of Lee Oswald talking to the Russian Consulate or whoever he was at that time asking for financial aid. Now, that particular transcript does not appear here and whatever happened to it, I do not know, but it was a lengthy transcript and I personally did that transcript. It was a lengthy conversation between him and someone at the Russian Embassy.

Genzman: How long do you recall this conversation was?

Anna: This conversation, I would say, at least covered a page and a half or two.

Genzman: Is it your recollection that the person speaking identified himself as Lee Oswald?

Anna: He definitely identified himself as being Lee Oswald.

Anna never changed her story, meaning a transcript the public has never seen — much longer than the two that the CIA made available — went missing. Since it was as long as two pages, did it say anything the CIA wanted to conceal? Had the KGB learned something operational that the impostor-caller conveyed over the phone?

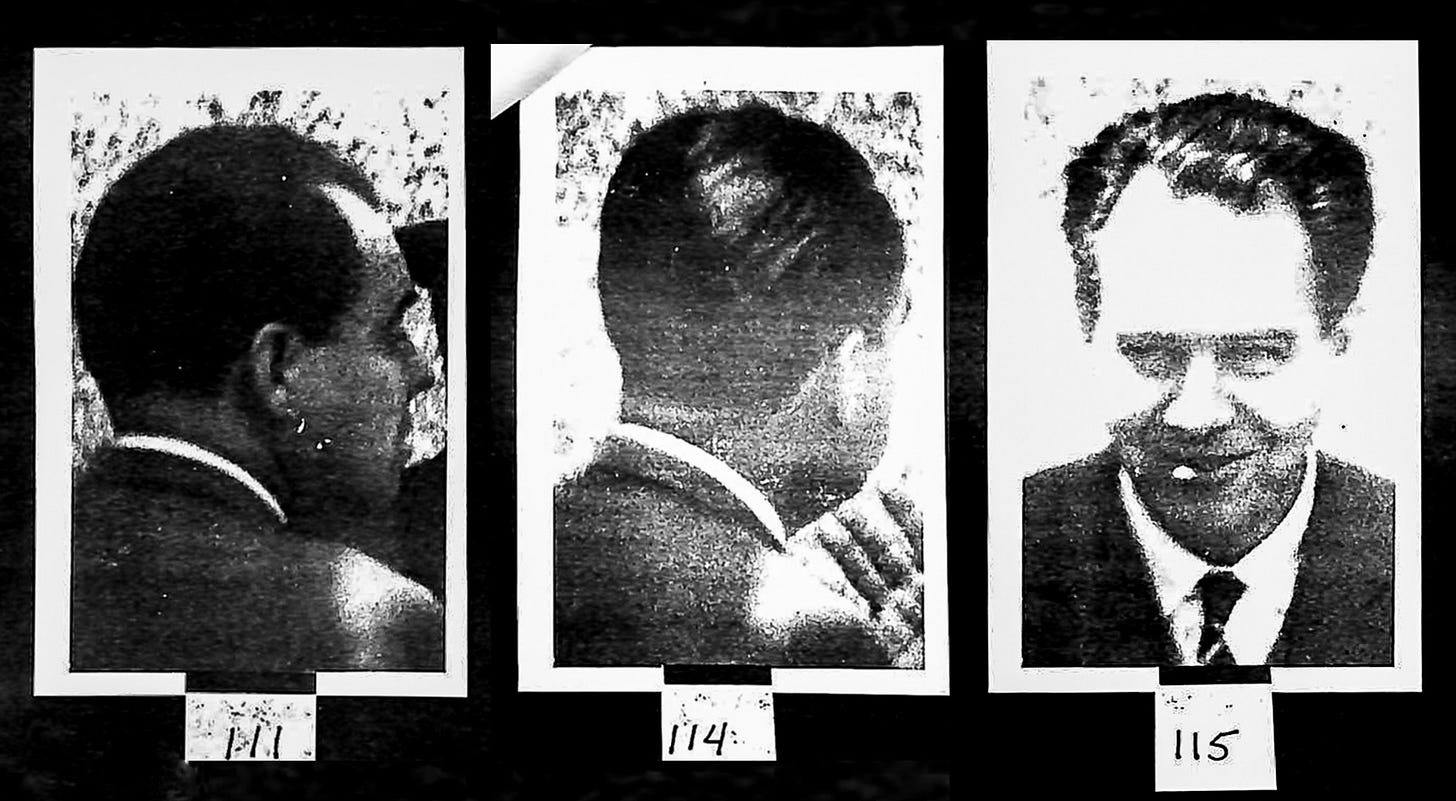

In the paranoid world of James Angleton, releasing any audio recordings of “Oswald” was a non-starter. Someone had impersonated his pawn over the phone, and it wasn’t anyone working for the CIA. Worse, Nikolai Leonov, a target of the CIA’s TARBRUSH black propaganda operation, had impersonated Oswald physically in the Cuban Embassy. If CIA photo surveillance agents captured pics of the real Oswald entering or leaving the Soviet and/or Cuban embassies, best to just bury or destroy them. The increasingly unsound spy chief’s last-ditch gambit was to just refuse to admit that the CIA even knew who Oswald was. Plus, there was that mole he still hadn’t caught (and never would) to think about.

The Victim Eyewitness

At the latest by the time of her HSCA testimony, Sylvia Tirado (Duran) Bazan recognized Nikolai Leonov as the man she had confronted on Sep. 27, 1963, presenting himself as Oswald and making a scene. But she maintained the pretense that it was the real Oswald.

Sylvia’s best friend among the main actors, Eusebio Azcué, described her as “a Mexican lady, but someone that the Cuban government fully trusts and also trusted by the consul that was going to replace me.” That “trust” meant they viewed her as a good person, or that they could rely on her to keep a secret — or both. After the “Oswald episode,” they urged her to protect the “counter-provocation” executed by agents of Cuba’s most important ally, the U.S.S.R., and to tell anyone who asked that the Oswald who appeared on TV and in the newspapers had also screamed and shouted at her on Sep. 27, 1963.

Twice victim to the “Oswald provocation” and forced to choose sides, Sylvia picked the more benign one, at least as far as she was concerned. Mexican security police had detained and interrogated her at the CIA’s behest immediately after the assassination, roughing her up physically, doing their best to terrorize her, and even trying to make her admit she’d had sex with Lee Harvey Oswald, a lie concocted by CIA Mexico City Station Chief Win Scott. She had told the Mexican security goons that the visitor was “blonde and short” (like Leonov), only for the CIA to excise her description from the version it gave the Warren Commission. In sum, the U.S.-Mexican side had treated her brutally.

The Soviet-Cuban side hadn’t. The KGB and G-2 might have been a bit scary at times, but they were an easy choice for her over the CIA, even in 1978. It was that simple. Apart from the fact that the U.S.S.R. was still Cuba’s powerful and vital global ally, Nikolai Leonov was still a serving, very senior officer of that ally’s premier intelligence agency.

Sylvia’s visual memory may have been poor too. She told the HSCA she wasn’t sure she recognized Eusebio Azcué Lopez’s replacement, Alfredo Mirabal Dìaz, in a CIA surveillance photo. Maybe she hadn’t interacted with Mirabal directly or often enough to be sure it was him, but he did work in an office adjacent to hers for three months.

Sylvia made other problematic statements to the HSCA as well. The now-familiar visa application photo shows Oswald in a cardigan sweater and tie with white shirt.

Cornwell: To the best of your memory, was he wearing the same kind of clothes that he was wearing that day in the photographs?

Sylvia: Yes.

It may have been “to the best” of her memory, but it didn’t match the testimony of a single other witness, Russian or Cuban. Azcué was even very precise, saying the visitor wore “a very light blue Prince of Wales suit.” Mirabal also said the visitor was wearing a suit. In the 1993 PBS Frontline documentary, Sylvia was still repeating her inconsistent account, wearing sunglasses, perhaps to avoid squinting under bright studio lighting but also making it easier to repeat falsehoods she had told the HSCA.

Sylvia may still be alive, and if so, hopefully she feels secure enough now to clarify the record. But for whatever reason, her statements in 1978 don’t add up. She was either an accomplice to a KGB/G-2 psyop as it was happening or — more likely — after the fact.

Subverting the FPCC

Ostensibly, Oswald still had the rest of his mission to fulfill. He was supposed to damage the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) in Mexico with a repeat of his performance in New Orleans in August. So what did he actually do?

We have no proof of where he went or what he did for the remainder of his time in Mexico. and no photographs of Mexico City were found in his possession after his arrest on Nov. 22, 1963. Whoever his “handlers” were for the Mexico trip probably told him to stand down after the embassy episode, abort the FPCC-subversion mission, keep to himself, and go home. Maybe he went to some bullfights or did some sightseeing, but that’s it.

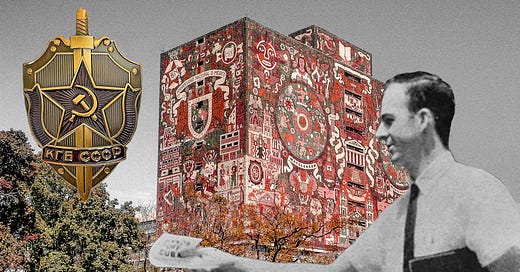

However, former HSCA investigator Dan Hardway, in a 2015 article entitled, “A Cruel and Shocking Misinterpretation,” offers a clue to the continuing Mexican adventures of “Oswald” after the embassy encounters. A law student and journalist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), often just called the University of Mexico, claimed to have met a “Lee Harvey Oswald” in Mexico City in late September 1963. His name was Oscar Contreras, and the CIA prevented the HSCA from interviewing him. However, Anthony Summers and others did interview him in the intervening years.

Contreras acknowledges that Oswald, in late September, 1963, approached him and three other students who were members of a pro-Castro student organization. He asked them for help getting a visa to Cuba from the Consulate. Contreras did have contacts at the Consulate and spoke to the Consul and an intelligence officer. Both warned him to have nothing to do with Oswald as they suspected he was trying to infiltrate proCastro groups. Contreras still wonders how Oswald identified him and his friends as the students, out of the thousands attending the University, as the ones with contacts in the Consulate.

Summers, in his book “Not in Your Lifetime” (2013), elaborates further:

One evening at the time of the Oswald incidents in Mexico, [Contreras] told the author, he and three friends were sitting in a university cafeteria talking. They all held leftist views, and he belonged to a group that supported the Castro revolution — as did many Mexicans — and had contacts in the Cuban Embassy. As they chatted, a man at a nearby table came over and introduced himself, spelling out his entire name — “Lee Harvey Oswald.” … Like Consul Azcue, Contreras said the “Oswald” he met that evening looked older than thirty, Like Sylvia Duran, he recalled that Oswald was short — he, too, thought at most 5’6”. Contreras, who was himself 5’9”, clearly recalled having looked down at the man… (“Not in Your Lifetimes,” p. 323-324)

For an excellent summary of this issue, read the 2023 essay by Gerry Simone, “A Narrative is Debunked” (Kennedys & King, Jan. 11, 2023). An early article by Michael Swanson, “Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City” (Fair Play, Issue #4, May-June 1995) also discusses the incident, and the discrepancies between the visitor and the real Oswald.

Contreras told interviewers very little of the “Oswald” encounter and said he feared giving details that might implicate his old comrades from the university. He and the others had “mistrusted Oswald immediately because they felt he was a CIA provocation.” Adamant that he wanted to go to Cuba, “Oswald” was “strange and introverted” and seemed “slightly crazy." He said he had already inquired at the Cuban Consulate about a “pro-Cuban revolutionary group at UNAM and was directed to Contreras and his friends.” Contreras “allowed Oswald to accompany them the rest of that day, that night (at group safe house) and part of the next day.” The encounter had made a strong impression on Contreras because of the later connection of Oswald to the Kennedy assassination.

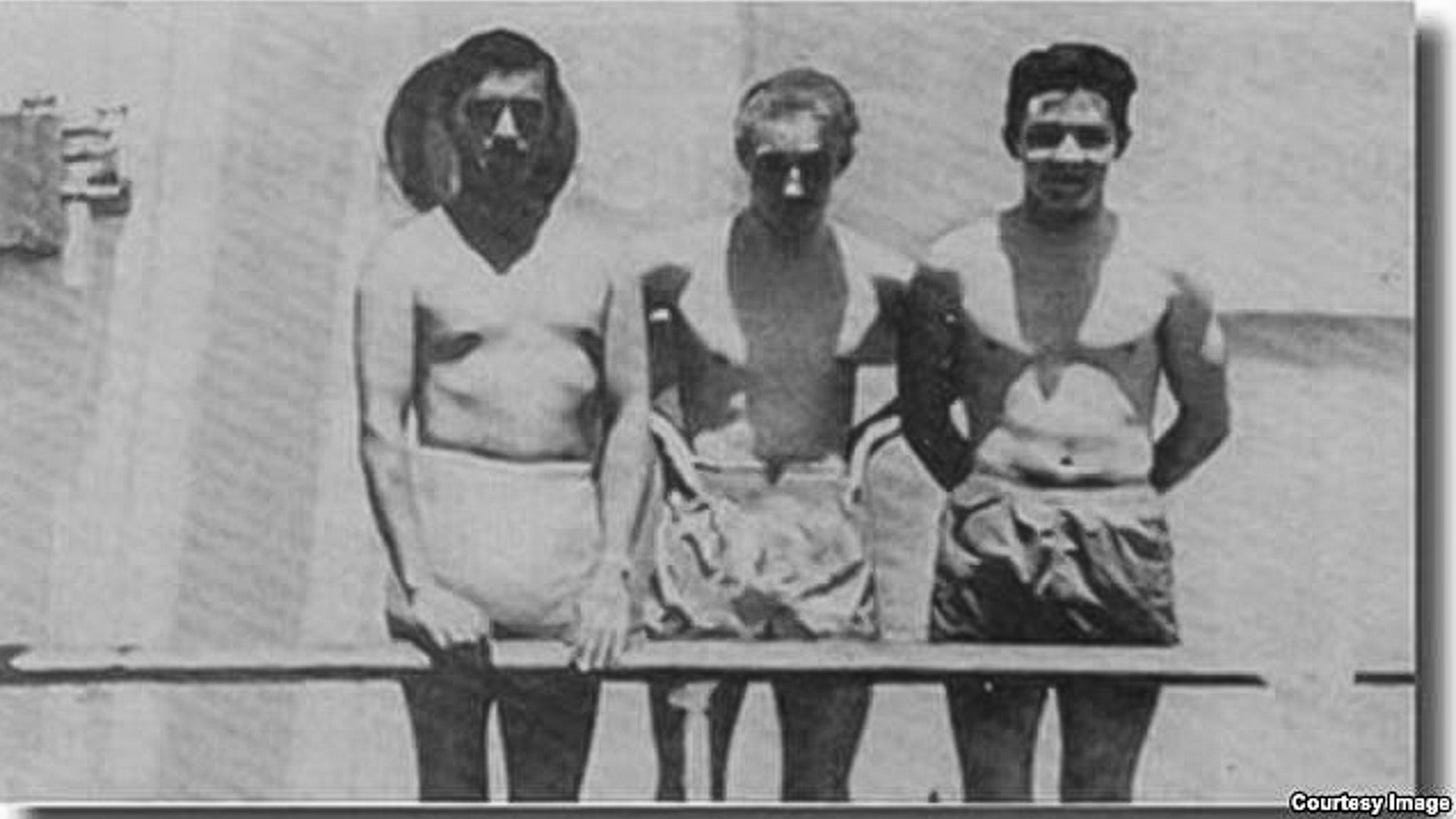

So how did “Oswald” identify Contreras and his friends? Well, it so happened that Nikolai Leonov was very familiar with UNAM. It was the university where he had studied when he first left Russia in 1953, befriending Raùl Castro en route to the Western Hemisphere.

Leonov fits the physical description of “Oswald” cited by Anthony Summers. Leonov was a very small man, as Sylvia Duran, Eusebio Azcué, and Alfredo Mirabal Dìaz all told the HSCA the “Oswald” in their consulate was. Online information indicates that Raùl Castro is only 5’7”, yet photos of him with Leonov indicate the Russian was even shorter.

It was Nikolai Leonov who met Contreras and his comrades at UNAM and posed as the American provocateur (and durak) Lee Harvey Oswald. Leonov put on an act as a strange, mentally unsound and unsettling presence for the Castro-sympathizing Mexicans, leaving them thinking he might be a phony. Sure enough, when Contreras checked up on him at the Cuban Embassy, he found his fears fully justified. The Cubans told him he and his comrades should stay well away from the weird American. The Leonov deception had ultimately confused both Contreras and his interviewers, but for the KGB it was mission accomplished. The CIA operation to subvert the FPCC — at least in Mexico — was a bust.

Significance of the Mexico Mystery

What happened during Oswald’s journey south of the border — at the time it happened — probably had nothing to do with setting him up as a patsy for JFK’s assassination. Whoever plotted to kill JFK had a “reserve” of fall guys, and Lee Harvey Oswald simply drew the short straw. Since one of the foiled schemes was scheduled for Nov. 18 in Tampa, the plotters only settled on Oswald as the “fall guy” four days before Dallas.

Once Oswald was arrested on Nov. 22, 1963, the government used that jaunt to paint him as a left-wing extremist, spur a cover-up to avert World War III (by hinting he might have conspired with the Soviets and Cubans), and facilitate his posthumous “lone gunman” conviction. That fulfilled President Lyndon Johnson’s wish to put the matter on the shelf and forget about it. The conspirators hadn’t decided to finger Oswald specifically by the time of the Mexico City episode, even if they were already planning to murder JFK.

That isn’t to say Oswald wasn’t “special.” On the contrary, Angleton already had a big and fast-growing file on him before the Mexico City episode. As an “agent of influence,” Oswald functioned as both a tool in a joint CIA-FBI propaganda operation to subvert the FPCC and a pawn in Angleton’s increasingly harebrained mole-hunt operations. But that just meant the conspirators could count on an official cover-up after JFK was dead.

On top of that, the Soviet KGB knew very well who Oswald was. He was still contacting their embassy in Washington as late as November 1963 about returning to Russia. He might not have known the CIA was using him as a provocateur in the Soviet Embassy, but to the KGB, he was both a provocateur and a durak. He stuck out like a sore thumb. In Russian, viyebnut — “screw” — is a profane verb. Oni nas viyebnuli. They screwed us.

Sick of constant provocations by U.S. agents of influence, all the KGB officers — Kostikov, Nechiporenko, Yatskov, and Leonov — who said they confronted Oswald in person recounted the tale as if the American was barely known to them. All lied. And at least one Cuban Consulate official — Alfredo Mirabal Dìaz — was in on the scheme before its execution. Sylvia Duran and Eusebio Azcué were more likely accomplices after the fact.

It was no mystery why Nikolai Leonov refused to talk to Americans in his retirement. Having instrumented the failure of the CIA’s provocation in Mexico City in 1963, he then watched his Cold War enemy kill its own head of state and pin the blame on a hapless pawn, Lee Harvey Oswald. That’s what the CIA mandarins opted for rather than admit their own failure, and they’re still doing it to this day — concealing failure over their use of Oswald for Angleton’s unaccountable schemes. The price of destroying the FPCC was a dead president who was increasingly popular in the Western Hemisphere. Nikolai Leonov, the central actor in a KGB counter-provocation in Mexico City remained disgusted well into his old age. A proud Russian spy who wasn’t afraid to criticize his own country’s government, he had no problem blaming the U.S. government for the death of JFK.

In any case, Rep. Anna Paulina Luna, chair of the House Oversight Committee’s Task Force on the Declassification of Federal Secrets, has said she will ask the Russians for the KGB’s surveillance files of Lee Harvey Oswald, and she should also request the report on Oswald from the Mexico City rezidentura on Sep. 28, 1963. Let’s wish her good luck.

Previous chapters of Oswald and the KGB appear at the following links: I, II, III, IV and V

By getting JFK out of the way, the CIA and Joint Chiefs hoped to have a free hand for war in Vietnam, invasion of Cuba, and carpet bombing of Russian cities over 25,000 with nuclear bombs. Once LBJ was in the saddle LBJ allowed Vietnam but none of the other baubles. The whole Cuban fiasco was merely to have something to wave at Americans to get political support for invading Cuba. Once the issue was moot, the issue was moot. We don't have any photos of Oswald in Mexico, and of course to convict him there would have been some made. The total total total lack of film confirmation strongly indicates and virtually proves Oswald was never in Mexico. Further, had he been there Mexican shadowing of the gringos would have likely produced Oswald documentation, but there seems to be none there either. QED, ditto QED.